Book Photos

___________________________________

NOTE: Johns Hopkins University Press, publisher of The Lupus Encyclopedia, is a nonprofit publisher. If you purchase JHUP books, like The Lupus Encyclopedia, you support projects like Project MUSE.

Lupus Pictures from The Lupus Encyclopedia, edition 2: Includes color images

Due to publishing restrictions, the photos from The Lupus Encyclopedia were published in black and white. This page includes the photos in color.

Includes photographs of cutaneous lupus affecting skin of color

Photographs of people of color (skin of darker pigment) are included. We need more photographs of cutaneous lupus (lupus affecting the skin) in people of color that are easy to find on the internet. Rashes in people of color are underrepresented in books and on the internet. It is important that they be published because it can be more difficult to notice redness (erythema) and pink-colored rashes on darker skin. I hope more healthcare providers publish their photographs of cutaneous lupus in people of color.

Why are most lupus pics done of white skin? It is because rashes are much easier to see. Unfortunately, this trend of making things easy left out the largest population of lupus patients. Lupus occurs much more often in people of African, Asian, Hispanic, and indigenous ancestry.

NOTE: If you have well-done photos of cutaneous lupus in people of color and would like to share them on this page (especially if that particular type of rash is not represented, contact Donald Thomas, MD for inclusion. You would get full credit, of course). The more photos accessible to health care providers and patients, the better

Page Contents with Links

1492 color woodcutting showing the Bishop of Liège being healed of lupus in the 10th Century by Saint Martin. The 1st person ever described who had lupus.

The Basilica of Saint Martin, Liège, Belgium. Build because the bishop was cured of lupus by Saint Martin.

Still life painting by Stephanie Smith who died in 1969 from systemic lupus. Anti-Smith antibody was named after her.

- Figure 7.1 Jaccoud’s arthropathy hand

- Figure 7.2 Ultrasound showing lupus inflammatory arthritis of the wrist

- Figure 7.3 Ultrasound showing lupus tenosynovitis that caused the Jaccoud’s arthropathy in the patient in figure 7.1

- Figure 8.1 Malar (butterfly rash) in a person of color

- Figure 8.2 Steroid rosacea, which can mimic the lupus butterfly rash

- Figure 8.3 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus in someone with systemic lupus (caused by the drug lansoprazole)

- Figure 8.4 Discoid lupus in a white woman with systemic lupus

- Figure 8.5 Discoid lupus on a person of color

- Figure 8.6 Lupus profundus (panniculitis) on the upper arm

- Figure 8.7 Lupus tumidus in a person of color

- Figure 8.8 Scarring alopecia (hair loss) due to discoid lupus (showing an actively inflamed lesion)

- Figure 8.9 Nonscarring alopecia that grows back after treatment of this patient’s severe systemic lupus

- Figure 8.10 Erythromelalgia

- Figure 8.11 Livedo reticularis on the arms

- Figure 8.12 Telangiectasia on the face

- Figure 8.13 Vitiligo on the upper back

- Figure 8.14 Increased skin pigmentation (hyperpigmentation) of the shins due to hydroxychloroquine

- Figure 8.15 Lichenoid drug reaction from hydroxychloroquine affecting a tattoo via Koebnerization

- Figure 11.2 Raynaud’s phenomenon

- Figure 14.1 Schirmer’s test to diagnose decreased tear production from Sjögren’s disease

- Figure 14.2 Thrush (oral candidiasis) and deep furrows on the tongue of a woman with Sjögren’s disease

LUPUS PICTURES FROM CHAPTER 1, Lupus Encyclopedia, edition 2

Mnemonic to remember the 1996 revised version of the 1982 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Someone needs 4 of these 11 criteria in order to fulfill the classification criteria

Renal (proteinuria, active urine sediment)

Arthritis (≥ 2 inflamed joints)

Serositis (pleurisy or pericarditis)

Hematologic (↓WBC, ↓Platelets, hemolytic anemia)

Oral (mouth) or nasopharyngeal ulcers

Neurologic (seizures or psychosis)

Malar (butterfly) rash

ANA positive

Immunologic (dsDNS or Smith antibodies; false+ RPR, LAC, ACLA)

Discoid lupus

Sun sensitive rash (photosensitive rash)

The mnemonic RASH ON MAIDS can help you remember the criteria used in the ACR classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. RASH ON MAIDS was developed by Donald Thomas, MD

Saint Martin and Saint Brice healing the Bishop of Liege of his lupus, “le loup,” in Tours, France at the Shrine of Saint Martin

Saint Martin and Saint Brice healing the Bishop of Liege of his lupus, “le loup,” in Tours, France at the Shrine of Saint Martin. Wood cutting is from the 1496 French book “La Vie et les Miracles de Monseigneur Saint Martin“. Image copyright Donald Thomas, MD; The Lupus Encyclopedia, edition 1, Johns Hopkins University Press

Saint Martin and Saint Brice Healing Éracle, the Bishop of Liège of lupus

The above beautiful wood cutting comes from a French book dated 1496, “Le vie et miracles de Monsigneur Saint Martin, translatee de latin en francoys.” This is a translation of a 12th-13th Century historical text on the Miracles of St. Martin called Miracula beati Martini. An anonymous author wrote this historical series and falsely ascribed it to Herbernus, Bishop of Tours. However, Herbernus lived in the 10th Century and was dead before Eraclius, Bishop of Liège, was alive. Therefore, historians say that the 12th Century Miracula beati Martini was written by a Pseudo-Herbernus.

See my other blog post about the Bishop of Liege, the first person with lupus here: https://www.lupusencyclopedia.com/first-case-of-lupus/

This wood cutting from the 15th-century French translation depicts Eraclius (Éracle), the Bishop of Liège, dying of lupus in the 10th Century. Above him are standing Saint Martin (whose tomb is depicted on the left) and Saint Brice (who was buried close by).

The page in the book before this page with the wood cutting states that the Bishop had a disease commonly called “le loup” (French for lupus). Therefore, we know that “lupus” was used as the name of a disease as early as the 10th Century. The Bishop wrote that his body was full of open sores that looked like the bites of a wolf (lupus in Latin).

The Bishop of Liège, Belgium travelled to the Shrine of Saint Martin in Tours, France. He prayed inside Saint Martin’s shrine for seven days and seven nights to be healed of his lupus, since he was close to dying from it. On the seventh night, the saints appeared. When he awoke in the morning, all his open sores were gone, and he was healed.

He then went back to Liège and built a church dedicated to Saint Martin. Today, you can go to Liège and see St. Martin’s Basilica (la Basilique Saint-Martin de Liège or Basilica of Saint Martin).

Erratum regarding the dating of the written history of the Bishop of Liege

NOTE: Most historical sources up to 2023 (including the first two editions of The Lupus Encyclopedia) have the dates incorrect on when the account of the Bishop was written. Most of them include dates from 855 AD to 916 AD, by Herbernus, Bishop of Tours. However, Herbernus was dead before Eraclius was alive. Most lupus history articles before 2023 kept repeating dates mentioned in previous lupus historical articles, most quoting the 1988 article by Smith and Cyr, which incorrectly ascribed the written story to Herbernus (but using the 12th-century Pseudo-Herbernus text as the source).

Donald Thomas, MD, visits the basilica built because the Bishop of Liège was cured of lupus

Note, this is not the original building. It burned and the building was rebuilt. Image copyright Donald Thomas, MD

For our Catholic readers: This is the location of the very first Fête-Dieu (the Feast of Corpus Christi). The first Feast of Corpus Christi was held here in 1246. Pope Urban IV, who was a prior archdeacon of the church, officially instituted the Feast of Corpus Christi on September 8, 1264 (the Thursday after Pentecost).

Inside St. Martin’s Basilica you can see this replication of the sarcophagus of Éracle (Eraclus), Bishop of Liege. The first person written down in history as having lupus. He was cured of lupus by Saint Martin in the 10th Century. The Bishop allegedly wrote an affidavit to the Catholic Church in 961 AD, describing how he was healed of his lupus. He became the bishop in 959 AD, so the miracle must have occurred between 959 AD and 961 AD.

Image copyright and photograph Gary O’Connor, JD

Still life painting by Stephanie Smith, the original anti-Smith patient

Stephanie Smith (for whom anti-Smith antibody was named) was an aspiring artist. She painted the lovely still image below and gave it to Dr. Eng Tan, the rheumatologist who took care of her (along with Dr. Kunkel).

(published with permission from Dr. Eng Tan 2021)

Chapter 7 Color Images from The Lupus Encyclopedia, edition 2

Lupus Arthritis, Tendinitis, and other Musculoskeletal Problems

Figure 7.1 Jaccoud’s arthropathy in a woman with severe SLE. This developed over many years due to uncontrolled lupus tendinitis and arthritis. Image copyright by Donald Thomas, MD

Jaccoud’s Arthropathy

Most SLE patients with arthritis and tendinitis will not develop deformities. Unfortunately, some will develop a problem where the tendons will be damaged from inflammation and slip over the joints, causing the above appearance. This is called Jaccoud’s (pronounced yah-KOOZ’) arthropathy. SLE is the most common cause of Jaccoud’s. See the photo above and the tenosynovitis image below (figures 7.1 and 7.3).

Jaccoud’s arthropathy is a reversible deformity in that the doctor can straighten them out during physical exam (called reversible deformities), but it is not permanently reversible. After the doctor releases the affected fingers, they revert to their deformed shape. When Jaccoud’s worsens over time, the joints can lose their mobility, leaving the person with “fixed deformities” that cannot be straightened out.

An example of Jaccoud’s arthropathy is figure 7.1. This is an SLE patient of mine who gave me permission to publish her ultrasound and hand photos.

Note how the end joints of the fingers are bent (flexed), and the middle joints are bent in the opposite direction (extended). This type of deformity is called a swan-neck deformity (it is the shape of a swan’s neck). When the opposite occurs (the end joint is extended and the middle joint is flexed), it is called a boutonniere deformity. When these deformities occur in the thumb joints, they are called Z-thumb deformities because the thumb looks like the letter Z.

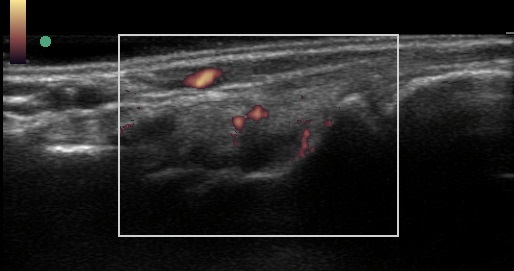

Doppler ultrasound of lupus inflammatory arthritis in a patient with systemic lupus

The image above shows a Doppler US photo of a lupus patient who has inflammatory arthritis of the wrist.

Many rheumatologists use ultrasound to help diagnose joint inflammation. It is one of the most accurate ways to tell if there is active inflammation from lupus.

In figure 7.2 above, the large white square in the photo is the area where inflammation can be identified using an ultrasound technique called “color Doppler.” Note the very bottom thicker white line closest to the bottom of the large square. That is the edge of wrist bone. The dark (black) oval-shaped area above it represents increased fluid and swelling of the wrist joint due to lupus arthritis. On the upper rim of the dark area are two small, connected orange circular areas. There is another orange area on the right side of the dark area that is also next to the wrist bone (thick white line). These are areas of lupus inflammation in the wrist joint, confirming that this patient has lupus inflammatory arthritis. Normal joints should not have these areas of orange.

Ultrasound examinations show that 25% to 75% of people previously diagnosed with noninflammatory arthralgia actually have joint or tendon inflammation.

Lupus Tenosynovitis and Tendonitis

Doppler ultrasound of lupus inflammatory tenosynovitis in the patient with Jaccoud’s

Figure 7.3 Ultrasound of one of the tendons of the above lupus patient (figure 7.1) showing active inflammation (the orange and blue dots). This is called tenosynovitis. Image copyright Donald Thomas, MD

Tendonitis (tendinitis) and tenosynovitis are also common in SLE. The tendons are sinewy, inelastic fibrous tissues that connect the muscles to the bones. When muscles contract, the tendons enable the muscles to move the much stronger bones. Just as lupus can cause joint inflammation (arthritis, figure 7.2), it can also cause tendon inflammation (tendonitis). Tendonitis usually causes pain around and between the joints. The joint pains seen in SLE are often due to tendonitis rather than arthritis.

A lubricating sheath surrounds some tendons. This sheath is called the tenosynovium, and it helps tendons glide more smoothly and stay in place. When these become inflamed, the condition is called tenosynovitis.

Lupus Tenosynovitis Ultrasound

A lupus tenosynovitis ultrasound is shown in figure 7.3. This (figure 7.3) is an image of the tendon that bends the index finger of the woman’s hand pictured in figure 7.1. In the center of the large white square, running from left to right, are a bunch of parallel white and black lines. They fill up the middle one-third of the square. These are tendon fibers. At the top of these lines, toward the left, is a thicker white line, then a small orange oval area and a blue area, then another thick white line above those. The space between the thick white lines is the lubricating surface between the tendon and its tendon sheath (thin piece of tissue) that surrounds it. The purpose of the tendon sheath is to keep the tendon in place and provide a lubricated surface for it to glide smoothly while bending the finger.

Normally there is little to no separation between these lines on ultrasound of a normal tendon. The space here represents increased swelling from lupus inflammation. The two round orange and blue areas are areas of lupus inflammation.

Note: The above text comes from Thomas, Donald. The Lupus Encyclopedia, edition 2, copyright Johns Hopkins University Press.

Chapter 8 Color Images from The Lupus Encyclopedia, edition 2

Cutaneous Lupus: Skin Involvement from Lupus

Malar (butterfly) rash: a type of acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

The malar rash (image above) occurs on those areas of the face that are most exposed to ultraviolet rash (the nose and cheeks). It typically spares the crease under the cheeks (nasolabial fold). Although this is the most well-known rash of systemic lupus, it only occurs in around 30% of patients with SLE.

Lupus Malar (Butterfly) Rash Mimics

Not all facial redness in people with lupus is due to malar rash. Other possibilities include acne rosacea (figure 8.2) and seborrheic dermatitis (a type of scaly skin inflammation). Oral steroids can also cause facial redness. Rosacea is commonly mistaken for the malar rash. It is essential to know the difference because the treatment of malar rash is very different from that of rosacea.

Dermatomyositis (a systemic autoimmune disease related to lupus that attacks the skin, dermato-, and muscles, -myo-) can also cause a rash mistaken for the lupus malar rash (especially in children). It is essential to check for muscle weakness on physical examination and high muscle enzymes (such as CPK and aldolase) in the blood work. These findings would suggest a diagnosis of dermatomyositis.

It often takes the help of a skin doctor (dermatologist) to correctly diagnose and treat rashes in people who have lupus.

NOTE: The above excerpt is from Thomas, Donald. The Lupus Encyclopedia, edition 2. Copyright Johns Hopkins University Press.

Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) occurs in two major forms. One appears as red, scaly patches, almost like psoriasis, and is called psoriasiform SCLE (also called papulosquamous SCLE, figure 8.3). The other form of SCLE appears as reddish rings and is called annular SCLE. When SCLE heals, it can leave some discoloration on the skin, though it does not usually cause the severe skin scarring and hair loss that occurs in chronic cutaneous lupus. SCLE is most prominent in sun-exposed areas such as the back, chest, and arms. However, it can extend to other areas, such as the buttocks. Face and scalp involvement rarely occurs.

Around a third of the cases of SCLE are due to taking medication; the condition is called drug-induced SCLE (DI-SCLE). If a person started any of the medicines that cause DI-SCLE even years before the rash began, the drug should be stopped to see if the rash disappears. Depending on the drug, the rash can start as quickly as 3 days after starting the medication, or as long as 11 years to develop.

Common Causes

Some of the most common causes of DI-SCLE include calcium channel blockers, thiazides, minocycline, and proton pump inhibitors (such as pantoprazole and omeprazole). Antifungal treatments, in particular, can cause DI-SCLE within a few weeks, while thiazides and most calcium channel blockers take much longer (months to years). DI-SCLE goes away or gets much better after stopping the culprit medicine, although it can take an average of seven weeks to improve. Most cases of DI-SCLE get better with the use of medications that calm down the immune system (immunomodulators). However, DI-SCLE due to proton pump inhibitors (PPIs, used to treat heartburn and ulcers) usually does not improve with immunomodulators; instead, PPIs should be stopped.

NOTE: The above excerpt is from Thomas, Donald. The Lupus Encyclopedia, edition 2. Copyright Johns Hopkins University Press.

Figure 8.6 Lupus profundus (lupus panniculitis) on the upper arm in a patient with SLE. When palpating this lesion, there is swelling (induration) underneath. This was tender and painful to the patient. Photo copyright Donald Thomas, MD

Lupus profundus (lupus panniculitis)

Lupus profundus is a type of chronic cutaneous lupus. It is due to inflammation of fat (panniculitis) under the skin. It can be quite painful to the patient. If not treated quickly, it can leave permanent loss of tissue under the skin, causing a large indentation. We usually call it lupus “profundus” rather than just panniculitis when there is involvement of the superficial skin by discoid lupus (like this patient has).

Lupus profundus is a type of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is the most common type of CLE.

Figure 8.4 Discoid lupus erythematosus on the cheek. Image copyright by Donald Thomas, MD

Discoid lupus erythematosus

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is the most common type of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. If not treated quickly and brought into remission, it leaves permanent skin damage and scarring. DLE starts off as small inflamed red or pink areas. Untreated, they grow wider. They are oval or round. This is why they called “discoid.” They are disc shaped.

Note how the border is red. It is actively inflamed and will continue to grow wider if not brought under control.

Note how the inside is a light color without the redness. This is permanently scarred, damaged skin. It can be very disturbing for the patient due to the cosmetic appearance changes. It is especially devastating when it occurs in people with skin of color.

Her discoid lupus was brought under control when her SLE went into remission on treatment. She was left with scarred areas of skin that was lighter in color, but the areas did not enlarge.

Figure 8.5 Discoid lupus on the ear and face of a black man. Image copyright by Dr. Ginette Okoye, Chief Dermatology, Howard University, Washington DC

Discoid lupus on skin of color

Lupus rashes can look quite different on skin of color (photo above and below) compared to white skin. Notice the differences between the discoid lupus affecting the cheek and ear of this black man cared for in the dermatology clinic at Howard University by Dr. Okoye.

Lupus rashes, especially erythema (the medical terms for redness), can be difficult to recognize on darker skin tones, as compared with light skin tones. While the erythema appears bright red in the latter, it may look dark purple or dark brown on darker skin. If it is overlooked, there may be a delay in diagnosing people of color with lupus and providing them with essential treatments. (Excerpt from Thomas, Donald. The Lupus Encyclopedia, edition 2, copyright Johns Hopkins University Press).

It is imperative that we treat these aggressively as soon as they are first noticed. Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) should be used in most patients. Cortisone creams and injections also help.

Discoid lupus on the arm of a black person. Image copyright by Dr. Ginette Okoye

8.8 Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) causing scarring alopecia in an SLE patient. Note the pink area. She is having a flare of inflammation in her DLE when this photo was taken. Image copyright Donald Thomas, MD

Scarring alopecia due to discoid lupus erythematosus

When DLE affects the scalp and destroys the hair follicles, hair loss (alopecia) occurs. These lost hair follicles can never come back, so the person is left with areas of permanent hair loss (scarring alopecia).

It is important that the person with DLE be treated quickly and aggressively to prevent permanent, cosmetic changes from occurring. People suffering from DLE have high levels of poor self-esteem and subsequent poor quality of life-related to these changes and needs to be taken seriously.

Figure 8.9: Nonscarring alopecia in a black woman with SLE during a severe lupus flare. Image copyright Donald Thomas, MD

Same woman as the above. Her hair grew back after successful treatment of her SLE. Since it is reversible with treatment, it is called “nonscarring” alopecia. Image copyright Donald Thomas, MD

Nonscarring alopecia

When SLE causes the hair follicles to shut down, rest, and stop producing hair, nonscarring alopecia occurs. It most commonly happens at the frontal areas. There are often brittle and fragile hair in the area of hair loss as well, called “lupus hair.” Since the hair follicles are still present under the skin, they can produce hair again when the SLE is treated successfully. Hair grows in cycles of around 3 months. So, it can take 3-6 months after successful treatment of SLE before hair growth is noticeable. The lupus pics above shows one of my patients who had devastating hair loss when she first saw me. With proper treatment of her systemic lupus, her hair grew back beautifully.

Figure 8.7 Tumid lupus (lupus tumidus) on the arm of someone with skin of color. Image copyright by Dr. Ginette Okoye.

Lupus tumidus (tumid lupus)

Lupus tumidus is classified as a type of chronic cutaneous lupus by most lupus skin experts. However, some think that it is a separate disease. The vast majority of tumid lupus patients do not have systemic lupus. In addition, the biopsy appears very different under the microscope compared to other types of cutaneous lupus.

It appears as purple/blue color areas of raised skin, similar in appearance to welts or hives (urticaria). With successful treatment, they tend to resolve.

Figure 8.13 Vitiligo on the upper back of a woman of color with SLE. Image copyright by Donald Thomas, MD

Vitiligo

Vitiligo is an autoimmune disease of the skin where the immune system attacks the cells that produce melanin (pigmentation). This leaves a lack of pigment in the affected areas. Note how there is a sharp demarcation between the light-colored skin and the surrounding normal skin with no inflamed or scaly borders.

Figure 8.11 Livedo reticularis in a woman with SLE. Image copyright by Donald Thomas, MD

Livedo reticularis

Notice the mottling of the skin above the wrists. This is an area of livedo reticularis. “Reticularis” comes from the Latin for “net.” Note how the mottling is “net-like.” This occurs from decreased blood flow to the skin when tiny arterioles are narrowed. It is more common in patients who are positive for antiphospholipid antibodies.

Figure 8.12 Telangiectasia on the face of a woman with SLE. Image copyright Donald Thomas, MD

Telangiectasia

Telangiectasia are areas of dilated tiny blood vessels under the skin. When you press your finger on one and lift it up quickly, it is normal skin colored but quickly becomes red again. This is due to your finger pressure squeezing out the blood from the blood vessels, causing the normal skin color to appear. Then when the blood rushes back into the blood vessels, they turn red again. This is a permanent problem that does not go away after successful treatment of the SLE. However, when a person goes into remission with treatment, the treatment can prevent new areas from forming.

Figure 8.10 Erythromelalgia in a patient with SLE. Image copyright Donald Thomas, MD

Erythromelalgia

Erythromelalgia is a rare complication of SLE. The appearance above itself is actually common in SLE patients, due to palmar erythema or cutaneous vasculitis.

However, erythromelalgia is painful (distinguishing it from common palmar erythema and cutaneous vasculitis). This patient would keep putting her hands under the cold water in the exam room. Erythromelalgia feels better in cold and worse with warmth (the opposite of Raynaud’s which is worse in cold). After treatment with aspirin and immunosuppressant therapy, this resolved.

Skin Pigmentation from Antimalarial Drugs

One of the potential long-term side effects of antimalarials (hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and quinacrine) is dark-colored skin patches (figure 8.14). They often appear brown, black, or black and blue. They tend to develop on the legs (especially around the shins), neck, and face. Increased pigmentation can also occur inside the mouth (such as the upper palate) and nails and especially in areas where bruising occurs easily. Taking blood thinners (such as aspirin and warfarin) increases the risk. The coloration may decrease when the dose of the medicine decreases, but it is usually permanent. Since antimalarials have so many benefits in SLE (chapter 30) and are the safest SLE drugs, it is preferable to continue treatment and put up with the skin discoloration

instead of risking a lupus flare by stopping the medicine.

Quinacrine can cause an unusual yellowish color of the skin, nails, and whites of the eyes in around 25% of people. The yellow tint does improve after the dose is decreased or after the person stops taking it. Patients and doctors should be aware that the condition can be mistaken for jaundice, prompting unnecessary procedures to evaluate the liver.

NOTE: The above excerpt is from Thomas, Donald. The Lupus Encyclopedia, edition 2. Copyright Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tattoos and Lupus

It is not a good idea for SLE patients to get tattoos. Although many tattoo artists use proper sterile techniques, infections can occur. These include hepatitis B, hepatitis C, Staphylococcus aureus (a skin bacterial infection), endocarditis (heart infection), and HIV. If someone is on an immunosuppressant drug, the occurrence of one of these infections could be dangerous. Some people can develop cutaneous lupus at the tattoo site. These cutaneous lupus lesions follow the pattern of the tattoo. Cutaneous lupus can even occur on tattoos placed well before the person had lupus. The medical term for these skin lesions occurring at tattoo markings (or other areas of skin damage) is the “Koebner phenomenon,” or “Koebnerization.” Tattoos can even be the target of attack from reactions to drugs used to treat lupus (figure 8.15).

A 2019 Spanish study suggested that tattoos may be safe for lupus patients who are in remission (or who have low disease activity) and who are not on steroids or immunosuppressant drugs to get tattoos. However, this was a small study. It would be nice to have a more extensive research study to confirm these results before telling our patients that tattoos are safe.

NOTE: The above excerpt is from Thomas, Donald. The Lupus Encyclopedia, edition 2. Copyright Johns Hopkins University Press.

Raynaud’s Phenomenon

If lupus causes the blood vessels of the fingers and toes to become narrow, decreased blood flow can occur in the digits with stress or cold exposure. These tiny arterioles normally constrict with stress or cold. Normally, enough blood flows that there is no problem. However, in the person with systemic lupus who has this, the decreased blood flow can cause fingertips to first blanch (turn white) due to loss of blood flow. This is followed by a bluish color (as above) due to oxygen being used up by the tissues (oxygen-deprived blood appears blue like in our veins). With rewarming, as blood rushes back in, the digits can sometimes become red. So, the order of color changes are white, then blue, then red. However, most patients develop only one or two color changes.

The Heart and Blood Vessels

Figure 11.2 Raynaud’s phenomenon in a woman with SLE. Photo copyright by Donald Thomas, MD

Sjögren’s Disease

Figure 14.1 This woman with Sjögren’s disease is unable to produce enough tears to wet the pieces of paper used for Schirmer’s test. Photo copyright Donald Thomas, MD

Schirmer’s Test

Schirmer’s test can easily be done in the exam room by rheumatologists to help identify dry eyes from Sjögren’s disease overlap syndrome in lupus patients. The pieces of paper are placed under the lower eyelid on the outer third of the eye. They are left there for five minutes at which time they are removed. A normal result in a healthy person is usually 15 mm or more. A positive Schirmer’s test for Sjögren’s is less than 5mm. 5mm to 9 mm is considered borderline.

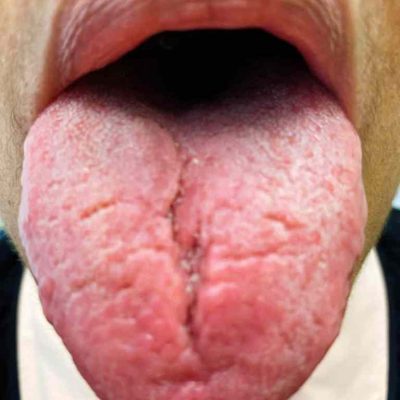

Figure 14.2 Oral candidiasis on the tongue of someone with SLE and Sjögren’s overlap. The deep furrows are due to the chronic dry mouth and the white coating is due to infection with Candida (thrush). Image copyright Donald Thomas, MD

Tongue in Sjögren’s with Thrush

Mouth dryness in Sjögren’s can cause the tongue to develop deep furrows. Think of when your skin gets wrinkly from dryness; it is a similar process. Decreased saliva leads to the loss of beneficial bacteria and bad organisms can take over such as the yeast Candida albicans. This is called thrush.

When there is some moisture, a white coating can form as in this patient. This is called “pseudomembranous candidiasis.”

However, in severely dry mouths, the yeast is unable to grow as much on the surface. Instead, it infects the tissues, causing a red colored tongue with a loss of papillae (the tiny bumps on the tongue surface) that is usually tender and sore. This is called “atrophic candidiasis.”